Introduction

142. It is not individual axioms that illuminate me, but a system in which consequences and premises mutually support each other.

- [Wittgenstein_2019], On Certainty

The initial problem of my master’s thesis was the issues that arise when the social stubbornly refuses to conform to our theoretical assumptions. We expect certain behavior or a displayed characteristic, but the person or even the group of people does not want to exhibit these qualities. For example, what happens if, through a Marxist lens, the subjects do not want or cannot experience their lives as alienated? Then we can change any of our assumptions; or theoretical terms are defined in multiple stages, e.g., alienation is divided into many sub-areas, and in one of them, the expected alienation can already be found; or we adopt an additional hypothesis that explains their deviant behavior: false consciousness. Conversely, if we are interested in not leaving the assumptions intact and saving them by adding a hypothesis, but rather changing the network of existing hypotheses through the deviant observation, we face the problem that we do not know which of the existing theses should be changed,1 because significantly more than just one hypothesis, along with some assumptions of an epistemological, ontological, or metaphysical nature, are necessary for the construction of a prediction; a decision on which of these frameworks should be changed is difficult to achieve and not directly derivable from the deviant observation.2 There is also often a lack of a clear overview of which frameworks to use and a way to directly compare different attempts to explain the deviation.

Among other things, my master’s project aims to address this deficiency, the overview of frameworks, and the lack of decision-making ability, and provide a methodological tool to break down and present theories in such a way that when considering an observation sentence, all drawn and thus to be changed sentences are enabled. For this purpose, requirements or limitations for a conception of theory as a network of sentences are derived in the work (central in Chapter 5).3 This theory network is not intended to be used to create monolithic, grandiose theoretical designs; they should be integrated into a network: The current research landscape of sociology is characterized by various loosely connected undertakings through central concepts. However, these can only solve the problems for which theory is formulated for a limited time and sometimes not at all. A shared theory, worked on a platform accessible to all, could facilitate the coordination of research results and the theoretical evaluation and classification of empirical findings, as well as provide empirical questions. This strand is deepened in Chapter 3.3 after incorporating system-theoretical vocabulary in Chapters 3.2.2 & 3.2.3 and speculatively continued in Chapter 6.3. The breadth of concepts treated here, the vocabulary used in wide circles of philosophy and sociology, especially system theory, as well as the breadth of included problem areas, whether in epistemology, methodology, or relevance explanation, demand a lot from the reader. Science, especially in theoretical consideration, and even more so in speculative release, is concerned with finding new forms; observing differences at the end of known meaning anew and making more visible. This clearly goes less far in everyday language. It is true that comprehensibility should not be a principle that prevents what can be said [Luhmann_1981 p. 176]. This does not mean that I have not written here with an effort for comprehensibility and connection of the readers; I have! Almost all major theoretical steps are prepared by several small and distributed steps. Terms are sometimes introduced multiple times to account for pauses in reading and memory. However, a high level of expertise is expected from the reader. It is aimed at scientists, mainly sociologists, philosophers, and social scientists, with knowledge in some sociological theories and basic knowledge in epistemology. Parts of the discussion, especially in Chapter 4, each require different forms of prior understanding to be fully comprehended. But even without this, much can be gained here. For someone with experience in ontologies of computer science, the chapter can be used to start approaches to creating a theory network with already known tools.

My project mainly resulted from the images Quine uses in the chapter “6. Empiricism without the Dogmas”:

The entirety of our so-called knowledge or our so-called beliefs, from the most casual objects of geography and history to the most profound laws of atomic physics or even pure mathematics and logic, is a human-made fabric that only meets experiences at its edges. Or to use another image, all of science is like a force field whose boundary conditions are experiences. A conflict with experiences at the periphery prompts changes within the field. Some of our statements must be assigned new truth values. The reassessment of a statement, due to its logical connections, leads to the reassessment of other statements - whereby the logical laws themselves are simply certain further statements of the system, certain further elements of the field.

- Quine 1951, p. 39; translation from Quine [Quine_2011], p. 117

This force field, or as Quine calls it elsewhere, this web-of-beliefs, is the starting and endpoint of my project; the questions arise: How can such a network of theses be mapped? How can this purely cognitively overwhelming demand be enabled by a cognitive framework? To clarify: The work aims at a methodological innovation that consists in the way of presentation and working method of creating theory networks. Furthermore, an epistemological argument based on Luhmann, Wittgenstein, Quine, Nicholas Rescher, and Susan Haack is pursued, which represents a cyclical, coherentist type of support for sentences within a network, with quasi-apodictic but not a priori valid sentences.4 The foundation will be based on difference theory: It begins with the fundamental existence of a difference; the foundation is the fact that differentiation can be made. It always sees differences situated in meaning and sees systems, which always refer to their environment, as necessary to process meaning. This foundation is carried out via Luhmann (e.g. [Luhmann_2011]; [Luhmann[1990] (2018)] and Jacques Derrida ([Derrida_1976]; [Derrida_2013]), mediated by Peter Fuchs ([Fuchs_1993]; [Fuchs_2003]; [Fuchs_2008]), who already connects both, as well as mediated by Marius and Jahraus, who in turn compare Luhmann and Derrida’s ‘super theories’ through Fuchs. The central influences, as well as the author5, are located in network thinking, which as a currently powerful worldview alongside the world view of neoliberalism, which has rightly fallen into disrepute in sociological circles, exists [August_2021 cf.].

In preparation for the master’s thesis, I was once again made aware of Niklas Luhmann’s sociological system theory. This contact changed the project in many detail questions, but the above, now written a year ago, exposition of the basic idea remains fitting. Not surprisingly, since Quine and Luhmann used quite overlapping sources (pragmatism, cybernetics) and were subjected to a similar zeitgeist. Furthermore, Luhmann has occasionally, but not insignificantly, referred to Quine’s considerations.6 Quine also pursued the project of a naturalized epistemology, which was centrally pursued biologically by Quine, also following Campbell. Luhmann takes up the project of a naturalistic epistemology and applies it sociologically. However, without sweeping away the other spheres. He presents the sociological epistemology, which mainly concerns the operation of meaning in social systems, and places it alongside, then rarely considered by him, biological epistemologies for living systems and psychological ones for psychic systems [Luhmann_[1984] (1991) p. 128]. The understanding of theory between Quine and Luhmann also shows parallels: For Luhmann, theories do not consist of what is laid out in books, or of laws and frameworks, or a network of concepts, but of sentences:

Theories are already subject to limitations in their form. They consist of statements (communications) in the form of sentences. Their performance therefore consists in the (dependent on concepts) predication. It is the conceptuality of the predicates that allows theoretical sentences to be distinguished from other sentences (which of course does not exclude that concepts can also function as sentence subjects). Concepts alone are therefore not yet theories. Theories are conceptually formulated statements, including statements about concepts, even if they do not have empirical reference.

- Niklas Luhmann, The Science of Society [Luhmann[1990] (2018) p.406] - Notes in the original

Elsewhere, in an introductory passage, Luhmann sees his problems in creating the lecture series and in writing books as being due to the fact that thought must follow thought. His theory conception pursues a rhizomatic logic, which here means a logic without a connecting center, without an unshakable central axiom.

Another problem is the necessity of linear representation. One thing comes after another. This does not really do justice to the theory pattern. Because what I have in mind is not a theory that, let’s say with Hegel: develops from the indefinite to the definite or self-determining or from axiomatic, abstract foundations to concrete applications, but it is more about a network in which more abstract concepts or new distinctions must always be introduced. The whole thing looks more like a brain, if you want to compare it, in which certain frequencies or influence lines run completely through, others are more localized. The order of representation is then relatively arbitrary.

- Niklas Luhmann Introduction to System Theory [Luhmann_EdST] p.14

The form of representation he seeks is that of hypertext; the inventor of the term hypertext, Ted Nelson, sees the same problems of arrangement. Linear representation becomes increasingly implausible with the internet; it only takes a subordinate local place in a globally networked order. We will return to this several times; especially in Chapter 4.4.

That sociology, both in practice and in teaching, requires theory seems hardly disputable. That empiricism requires theory and every theory requires empiricism has been clear at least since Kant.7 With Hirschauer, it is rather that every theory is “empirically loaded” [Hirschauer_2008]. The connection between theory and empiricism is rarely direct and not obvious; this is also reflected in a common division of labor between theorists and empiricists. But what exactly theory means, and what exactly the practice of theorizing entails, is part of an ongoing negotiation of the discipline. The creation and work on theory is rarely centrally addressed in the study of sociology, but also in sociologicalliterature.8 The central importance of theory, as well as its connection with empiricism, is repeatedly emphasized, but tools for working on and with theory are still a rarity. In my master’s thesis, I want to create a tool or toolbox, along with a methodological discussion of its creation and application, which serves to explicitly represent theories. Depending on the epistemological foundations and understanding of theory applied, different types of applications, but also forms of the tool, could be designed.

The theory network I envision stands, one could say, in the intellectual lineage of the Zettelkasten method. In the Zettelkasten, thoughts, ideas, concepts, etc., are noted in a concise but as permanently understandable form as possible on individual note carriers, in Luhmann’s case index cards, currently more commonly in Markdown, short .md, files, and connected with other index cards; various logics of connection are in circulation: One could break down the writing of a connection if another note is suspected to be explanatory or beyond it. The proposed network of theses is very similar to the Zettelkasten method; however, the specifications on the content of the notes and connections are much more restrictive, limited. With Wittgenstein, theories can be observed as nests of sentences, as sentence nests:

225. What I hold on to is not a sentence, but a nest of sentences.

- [Wittgenstein_2019]

A beautiful image: We imagine a Luhmann returning from his travels to his crow’s nest and integrating a few sentences into his nest. Other theorists would remove a few rotten branches here and there, but we know from Luhmann that a Zettelkasten always grew larger; forgetting occurred through not finding in the nest, not through sorting out. Some theorists like the glow and sparkle of beautiful illustrations, which they hang near their nests. Others seek beautiful long quotes, foreign feathers, with which they make their nest warm and less prickly. The Zettelkasten is a method to collect, organize, and connect ideas, concepts, and insights from reading and conversations. The theory network, on the other hand, is a method to process, present, and make theories, as a rhizomatic network of sentences and their connections, usable for further processing steps. We maintain a nest of sentences; but not all sentences will appear in it. Some are retained as evidence, as discarded. Some sentences stand behind the network level for description and clarification. Some sentences must stand outside the network for decision, just as the branch on which the nest is carried cannot become part of the nest.

Since the work with theory and empiricism permeates all of sociology, many fields of application and improvements can be found: For example, the theory network can be used as a means for working on paradigms in the Kuhnian sense [Kuhn_2020]; or paradigm work in the sense of Merton and following his CUDO9 norms [Merton_1974]. Here, the explicit representation of theories in a shared, accessible form of a website facilitates the shared “communist” work on theory. The joint work on concepts is favored, and the collection of supporting and refuting empirical evidence and their shared discussion and classification is facilitated. The functionality could be expanded to include a version history: With collectively established versions, which could be decided collectively after significant changes, research papers could enable a traceable disclosure of the underlying theory even later. Even without version history, a widespread tendency in sociology to reinvent the wheel [cf. Abbott_2001 p. 16-17], through the conservation and sorting of previously known concept constellations, would be alleviated. This leads to another advantage, the use as a means of reflexivity. Since work without assumptions is not possible, the only way is to accept, disclose, and reflexively consider them to change them if problematic. Through the theory network, one’s assumptions are made explicit. Changes in assumptions based on observations become more visible; thus more manageable.

The idea of theory as a network of sentences, as large as possible, has been in science at least since Quine’s widely received paper. Therefore, I was surprised that no implementation of such a project had yet been presented. It seemed to me and still seems that the size, the sheer workload required by such a project, is the biggest hurdle. The feasibility seemed algorithmically solvable to me; after some attempts with prototypes, I can say: It works. However, the resolution of each sentence and the connection is always contingent. An outsourcing to stochastic procedures does not seem expected in the near future. However, I was able to identify a precursor project that very precisely attempted my project: Jürgen Klüver announced the appearance of a collaboration with D. Krallmann in 1991, which, as far as I could see with computer-assisted search procedures, did not appear. In this, the development of a knowledge-based system for comparing formally reconstructed sociological theories was to be presented. To describe this project, Klüver wrote: “To support the formal reconstruction of individual theories, we have therefore planned to develop special knowledge-based systems, i.e., computer programs, that enable detailed reconstruction and corresponding detailed comparison in the first place” [Klüver_1991 p. 220] and further:

The term ‘computer-supported theory comparison’ in this context means that (a) the logical basic structures of individual theories are reconstructed according to the metatheoretical framework, (b) a special program system, a so-called knowledge-based system, is developed for each reconstructed theory, which includes the reconstructed theory structures as components of its knowledge base, and that (c) a “meta-system” is developed as a knowledge-based system that can perform formal structure comparisons between the individual reconstructed theories, more precisely: their implementation in the theory-specific knowledge-based systems.

- [Klüver_1991], p. 220-221

It seems to me that the rather high formal requirement, the resolution of logical basic structures, causes most of the problems. The most common logics can rarely handle necessarily occurring loops and cyclical justification structures. They are suitable for recording Aristotelian, or Euclidean systematics. Systematics, as modern sociological theories exhibit, can accommodate circles. They must be able to do this. Between society and the individual, no clear hierarchy can be observed; both are conditions for each other. Changes in one will result in changes in the other. We will return to this in Chapter 5.6.

Travel Description

The work aims to a) explore the tension field between theory, network, and system, b) plausibilize a concept of theory as a network of relatively rigidly limited sentences, c) illuminate and highlight previous and alternative conceptions and projects of theory networks, d) plausibilize sociological system theory as a suitable foundation for a network resolution of theory, and e) designate a shared theory wiki as the indicated form of self-processing of theory in the scientific system.

Ad a): The terms are frequently used throughout the work and in various meanings. Chapter 4 primarily deals with the concept of the network. In Chapter 5.1, a historical line of the theory concept is pursued. The entire Chapter 5 methodologically addresses the concept of theory. Ad c): It also includes the subchapter Theory: Collection of Classifications (5.7), in which all classifications of theory included in the work are juxtaposed. There are several. System and systematics, as well as the network, are discussed in parts with reference to Luhmann and Wolff. Ad b): Chapter 5 elaborates on the advantages of definitions for working on theory. It provides reasons why a strict representation as a network of sentences has advantages over vague versions and advantages over networks of concepts (especially in Chapter 5.8). At the same time, however, it is also shown, among other things, through the juxtaposition with numerous other understandings of theory (see above c)), that theory can always be understood differently and that it often has its justification and useful cases to use a different conception. Ad d): It is made plausible, based on the current state of sociology, that sociology cannot satisfactorily perform its memory functions in the form of loosely coupled “New Social Theoretical Initiatives” [Anicker_2022], but that no major social theory can deliver the necessary pace to take over these functions in a time of “economization, bureaucratization, managerialism, or transnationalization” [Heilbron_2014; Sapiro_Pacouret_Picaud_2015; Slaughter_Cantwell_2012] [Schmidt-Wellenburg_Schmitz_2023 p. 532], as well as the significantly increased publication density of science. Therefore, it is made plausible that a theory wiki10 can perform the memory functions of science well. The partly excursional considerations of the chapters are, quite commonly, summarized at the end of the chapters.

The central results of the work are collected in Tables 7 & 6, in Chapter 6.3, as well as Table 9. I would also like to mention the recommendation of Foundherentism in Chapter 5.6.2 and the comparison between a network of concepts and a network of sentences in Chapter 5.8. Depending on the application case and the auxiliary conceptions used, or the background of the reader, central starting points are found in other chapters. For application cases, see also Table 8.

The goal of creating the network is not a fixed representation of irrefutable truth; not the creation of a stone object that, decaying and needing our care, costs us more effort than it can show us new things; stands more in our way than it enables us to step to new shores. The network is rather intended to serve an ecology of exploration; it thus serves Plessner’s image of man as eccentric positionality: A series of rhizomatically interconnected, directly and through the theory network interacting individuals use intentionally fixed, always conceived as changeable and falsifiable statements and their connections to design, evaluate, or classify empirical observation. Neither theory nor empiricism has the upper hand: The network and empiricism always impact each other. The ecology is also affected by fluctuations: Trends, fashions, seasons will favor the processing of some nodes, will centralize the forms of some currently appearing apodictic statements, will bring previously forgotten things back to the forefront or let what was considered central fall out of hand. Luhmann’s theory was chosen, among other things, because it assumes itself, as well as everything else (social), to be included as a super- and universal theory; this seemed to me a necessary condition for the network’s performance in the aftermath of the Duhem-Quine hypothesis. Even though it is clear from the outset that I alone, and even a large group of researchers in a 30-year research activity with costs many, must fail in the task of creating a network for all knowledge, the fundamental matter of the possibility of doing so is nevertheless required. This requirement of epistemological holism of the network was reduced to the fact that both difficult-to-change, seemingly apodictic sentences (angel sentences, a priori sentences), as well as contextualized, empirically testable observation sentences and some in between, should be found in a theory network. So instead of a holistic network, a cross-section is aimed at. To return to the image of petrified concepts: Luhmann’s double volume The Society of Society is occasionally referred to as the two “tombstones of system theory”11. This work does not want to devote care, no presentation of flowers and respectful distance, no tradition maintenance. Rather, the network should serve the understanding of the double volume as a “compendium of system-theoretical theory resources” [Baecker_1998] and prepare the resources for a bricolage of further use, respecification, and rearrangement, to favor a flourishing instead of a petrification of system theory, and thus also of sociology.

Theory as a Network

In this section, we will approach some things. We will make the concept of theory plausible as a network of sentences, in which various classics of modern philosophy, mathematics, and sociology come to speak with a corresponding version (Chapter 2.1). We will present network thinking as a paradigmatic scheme that sought to replace the no longer, but in a resurgence of reactive forces, plausible sovereignty thinking (Chapter 2.2; this will anticipate the requirements for a theory for the 21st century (Chapter 3.1) as well as the consideration of the precursors (Chapter 4). The Quine-Duhem hypothesis will be taken up again, and here the later elaborated typology of sentences will be prepared (Chapter 2.3) and with maps, mazes, and (de-)signs some central metaphor spaces in thinking about theories will be opened (Chapter 2.3.1). Finally, a demonstration model of a theory wiki12 and a brief explanation of the intended functions will be presented. The theory wiki will be reflected on its fit to the current conditions of the scientific enterprise in Chapter 3.3 and speculatively anticipated on possible developments in Chapter 6.3.

Quine, Wittgenstein, Schlick & Luhmann: Theory as a Network

Two versions of theory as a network of sentences have already been encountered here: The work began with a citation from Wittgenstein’s On Certainty. With the preceding aphorism, an even stronger impression develops:

141. When we begin to believe something, it is not a single sentence, but a whole system of sentences. (The light gradually dawns over the whole.) 1.42 Not individual axioms make sense to me, but a system in which consequences and premises support each other.

- [Wittgenstein_2019]

A theory cannot be understood as a whole at once. One sentence must be read and grasped after another. Sentences must be questioned for their consequences for other sentences. Objects believed to be known must be viewed in a new light and repeatedly turned before they are understood. Here, a forward and backward grasping of the examination of sentences against each other becomes visible. A single sentence alone cannot be a theory. We need other sentences to connect, test, and understand it. Sentences cannot be added individually; they always come with further assumptions and conclusions that implicitly follow from them. Wittgenstein’s version can count for any system of sentences. This can range from language games known only in a specific group to worldviews; theories are just one such system of sentences. Much more rigid and formally logical is the version of axiom systems, as developed by Ernst Zermelo, an important founder of parts of the Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory, which underlies almost all parts of modern mathematics and logic:

Every axiom system A determines as the totality of its consequences a logically closed system, i.e., a system S of sentences, which already contains all sentences logically derivable from it. If such a system is consistent, i.e., free of contradictions, it must also be realizable, i.e., representable by a model, by a complete matrix of the basic relations occurring in the axioms or the system.

- [Zermelo_2010n p. 360].

Some of the central facts of sociology require the breakdown of self-references: actors who repeatedly refer to their own behavior; productive contradictions of society; autopoietic systems in self-reference; social institutions that reproduce themselves through and thanks to their performances; social processes, such as self-fulfilling prophecies. Therefore, freedom from contradiction and a stringent derivability of all sentences will not be achievable. A theory that explicitly incorporates such loops is Luhmann’s system theory. Here, too, theories are described as networks of sentences:

Theories […] consist of statements (communications) in the form of sentences. Their performance, therefore, consists in predication (dependent on concepts). It is the conceptuality of the predicates that allows theoretical sentences to be distinguished from other sentences […]. Concepts alone are therefore not yet theories.

- [Luhmann[1990] (2018) p. 406] - Notes in the original

An understanding of theory that comes very close to the use developed here is that used by Moritz Schlick, one of the leading figures of the Vienna Circle, in his attempts to develop a philosophy of nature: “Theoretical science consists of theories, i.e., systems of sentences” (quoted in: [Koenig_Pulte_2017]; [Schlick_1948]). Schlick uses this formulation as systems of sentences in his lectures on the philosophy of nature in the semesters 1932/33 and 1936. Here, sentences or statements are connected into a system by “dealing with the same objects, or even being derivable from each other” [Schlick_2024 p. 613]. This mutual derivability will later become a component of the understanding of theory, not in a deductive but in a cybernetic manner; thematic sorting will also become a classification feature. Schlick also points out the necessary hypothetical nature of theory, as it always consists of components gained from inductions, and no logically valid conclusion from the particular to the general exists. “All natural laws have the character of hypotheses [or assumptions]. Their truth is never absolutely certain. Thus, natural science arises [through] the interaction of brilliant guessing and exact [measuring]” [Schlick_2024 p. 614; insertions in the source].

A recent version offers the definition of theory from the scientific-theoretical foundation for Empirical Social Research by Günter Endruweit:

A theory is a system of sentences with statements about reality, which reproduces factual relationships through linguistic assignment.

- [Endruweit_2015 p. 20]

What bothers us here, and will bother us even more with Luhmann, is the fixation on the linguistic assignment to things, i.e., the objective reference, as well as the fixation on statements of being, i.e., ontology; I cannot go along with either. In Chapter 5, we will methodically approach theory and its components, sentences, as well as their components of concepts and predications. As a first result, we can note here that a theory requires more than just interconnected concepts and that more than one sentence must be present. The sentences must be connected into a network of sentences that support each other to provide performances for conviction, understanding, and empirical verification. It should be noted here that network and system were synonymous terms in their origin, which have repeatedly developed apart and back together in their meanings [cf. August_2021 p. 380]; both are central metaphors of network thinking (ibid.):

Network Thinking

“The paradigm of sovereignty was connected to modernity and the associated belief in enlightenment in social, societal, and political theory. […] The idea was that the mandate of sovereignty was accompanied by a teleological goal. Sovereign power legitimized itself from a sovereign goal (télos), according to which individual and societal ‘development’ had to be directed to realize ‘human nature’ and the ‘essence’ of human coexistence. […] This governance thinking of sovereignty was thoroughly humanistic, and a deformation of humans by technology had to represent a danger” [August_2021 p.17].

It becomes apparent that the paradigm of sovereignty failed not only structurally but also intellectually in its own promises, so that the conflicts over a normatively correct and factually stable order, just settled after 1945, reopened. The institutionalist and neo-Marxist interpretive patterns that had previously shaped political disputes with the help of sovereignty theories attested to a certain helplessness. Consequently, they were challenged and often replaced by two new interpretive patterns: On the one hand, neoliberal intellectuals criticized the state’s lack of rationality using public choice theory and wanted to reverse the hierarchy of state and market society. On the other hand, cybernetically inspired crisis diagnoses criticized the outdated rationality of modernity, which now failed due to its own successes. The complex, differentiated society could no longer be hierarchically controlled by politics. It needed a “new thinking” that was appropriate to the complexity, contingency, and connectivity of society.

- [August_2021 p. 20]

These crisis diagnoses are shaped centrally by cybernetic thought figures, alongside “technological artifacts and [the] technological [governmental thinking]”, as well as network thinking; the central technologies of information processing and telecommunications, currently still through the Internet and ‘AI’ [cf. August_2021 p. 19 & FN 19], remain in unbroken continuity with cybernetics. “Among these cybernetically inspired interpretive approaches are also the writings of Michel Foucault and Niklas Luhmann[. …] Thinkers whose ideas had an immense impact on the entire breadth of the humanities and social sciences” (ibid. p. 20). Poststructuralists and cyberneticians have more in common than is generally assumed. In Chapter 3.2, we will show the parallels between Luhmann’s system theory and so-called ‘poststructuralists’.

“Just as for Foucault, the king’s head must roll to enable an analysis of decentralized and widespread power relations, so must it be about the ‘death of the author’ as the guarantor of the unity of knowledge” [Stäheli_2000 p. 53]. Instead of the author, or the search for the sovereign of theory, the work wants to propose a democratic alternative. The gain in simplicity, which is indeed achieved by reducing to one person, can be countered by “the technological ‘standard argument’: Everything is much more complex” [August_2021 p. 22]. Rather, it should be proposed here, also expected in the current time, that theory should be worked on in the form of networks of sentences, which are available on a platform for research groups or even everyone, to collect empirical results, positive or negative evidence, as well as new theoretical sentences.

Avoiding the Quine-Duhem Hypothesis

The seminal text by Quine represents a central point in analytical philosophy. For many analytically inclined philosophers, the ‘hunt’ for a foundation on which all knowledge can be anchored is finally ‘called off’. The text is like a nail in the coffin of the project of the irrefutable world theory of modernity. Willard Van Orman Quine sees modern empiricism characterized by the Two Dogmas of Empiricism: A) The belief in a fundamental gap between truths that are analytic, or grounded in meanings independently of facts, and truths that are synthetic, or grounded in facts. [B)] The other dogma is reductionism: the belief that every meaningful statement is equivalent to a logical construct of expressions referring to immediate experience” [Quine_2011 p. 57, emphasis in the original]. In this very influential essay, Quine draws the consequences of withdrawing the foundation from these dogmas. We want to observe this as successful - unsurprisingly, this was also observed differently - and use the stones of the ruins to build something new. Quine, for his part, draws the consequences that “the supposed boundary between speculative metaphysics and natural science becomes blurred. Another consequence is a step towards pragmatism” (ibid.). The central naturalized epistemology in Quine’s work is thus only consistent. We will later see in Luhmann that, especially at the boundaries of meaning, but also with concepts such as autopoiesis, form, medium, etc., the boundary between metaphysics and sociology is difficult to draw; what else but meta-sociological is the inference to a necessarily, but unobservable, underlying medium behind every form? In Social Systems, Luhmann also takes up the idea of a naturalized epistemology; he turns it more towards sociology - Quine primarily towards psychology.

Like Quine, we want to state that some sentences lie more centrally and sacredly to us than others: There are sentences that are so important that they are quasi-apodictic, i.e., only irrefutable if very many good reasons are present. This could be observed with Kuhn as a scientific revolution, as a paradigm shift [Kuhn_2020], when some interconnected sentences are exchanged; or less reversibly, i.e., revolutionarily, when the exchange can be carried out by a few, and above all small, adjustments, as in the case of the foundation of mathematics in Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory and its adjustment from Zermelo set theory.13 Most of the existing proofs of mathematics were not affected. Much more revolutionary was the sweeping away of the ether theory, which was accompanied by the shift to the particle-wave duality of light14.

These central sentences, such as those of logic or cosmology, will later be seen in agreement with Wittgenstein’s angel sentences (cf. Chapter 5.5.2) and mark that these sentences enable a very similar function to the sentences a priori that no longer seem possible to us: They provide us with a foundation, an anchor point from which further theoretical and empirical decisions can be made and from which a network of sentences can be spun, which can be further refined based on coherence (cf. Chapter 5.6.1). At the other end of the ‘Web-of-Beliefs’, Quine sees observation sentences. Sentences that would be affirmed by competent speakers with similar expertise in concrete situations are true observation sentences for him [Quine_Ullian_2009 15-19]. In between lie further sentences that are derived, framing, or otherwise relationally connected to other sentences. The conclusion of confirmation holism and the indeterminacy of the consequences of a deviant observation (cf. Chapter 1) are problematic. Formally, the demand of holism holds that the entire ‘Web-of-Belief’ must be known to be absolutely certain that a deviant observation brings about the correct changes in our sentences. Pragmatically, we must and can be content with less than absolute certainty. We can collect a smaller part of very likely relevant sentences and keep the rest, as usual, in the vague background of the episteme or the house of the world view. In a very helpful collection of citations, Verhaegh summarizes that Quine still considers the thesis of “Duhemian holism” to still be true in principle, but in this form he holds it as “unintestingly”, als well as “needlessly strong” [Verhaegh_2018 S. 137]. Let us once again seek advice from Wittgenstein’s aphorisms:

212. For example, we consider a calculation to be sufficiently verified under certain circumstances. What gives us the right to do so? Experience? Could it not deceive us? We must stop justifying somewhere, and then the statement remains: that we calculate in this way. 213. Our experiential statements do not form a homogeneous mass.

- [Wittgenstein_2019]

Wittgenstein sees the stopping condition in habit or in the reference to the experienced self-evidence of the rules of the language game. He also refers here to relatively central sentences; which can be seen as partially overlapping with the later central anchor sentences. Experiential statements and even the foundation of a worldview do not have to be homogeneous with Wittgenstein, and presumably, do not have to be stringently connected, nor stringently recorded for all theories. What is presumably sufficient for us are some relatively securely acceptable sentences around which the network is linked for coherence and tested against empirical material. These considerations are continued in Chapter 5.5.2. The considerations on confirmation holism, and whether it can be circumvented with emergence and autopoietic sense organization of structure-determined systems, complicated by their interpenetration and structural coupling, cannot be sufficiently reflected upon in this work. The reasons for confirmation holism are good and strong. However, they are also pragmatically unfeasible. To make complexity manageable, cognitive reduction is necessary. Models must be created that reduce what is captured by the models. The well-known saying “A map is not the territory.” usually addresses this insight. If a map had the same resolution as reality, it would be useless. But if we look at the context of the quote, two other relevant aspects become visible:

Two important characteristics of maps should be noticed. A map is not the territory it represents, but, if correct, it has a similar structure to the territory, which accounts for its usefulness. If the map could be ideally correct, it would include, in a reduced scale, the map of the map; the map of the map, of the map; and so on, endlessly, a fact first noticed by [Josiah] Royce.

- [Korzybski_1933 p. 58]

Thus, reduction is the utility. If too many sentences are added, a representation of object areas becomes so confusing that the object area could be viewed directly. If the reduction is too crude, relevant aspects fall out of consideration. It is important to find the right measure of reduction for the respective task with a delicate touch and a lot of concrete experience.15 In the theory network, the sentences associated with a sentence should be displayed. This would make it easier to check the context and overlooked or alternative explanations. With a pragmatic stopping instruction, for example, only sentences that are directly or indirectly connected could be displayed; or only causally effective sentences could be displayed, etc. The second insight of this quote is the insight that led Luhmann to formulate the requirements for super theories: If theories contain the area in which theories or themselves are included, this must be taken into account. To avoid an autology, whether paradoxical or tautological, one’s own standpoint cannot be disregarded. A theory that wants to be as far-reaching as a sociological theory must be, needs a place for knowledge, knowledge dynamics, and thus theories, including itself.

Excursus: Map, Maze, Throws

Wittgenstein uses, as shown by Sybille Krämer, centrally the metaphorical space of the labyrinth: “For the fact that philosophy has to open up the knowledge of ways out of the labyrinth of not-knowing is the problem constellation as its solution and dissolution the key concept of the clear representation for Wittgenstein aims.” Remaining in this image of the labyrinth, the dead ends could be an artifact of the dimensional limitation of the plane; The dead ends are in the contexture16 - understood here as the area that can be appropriately described within a theory or a theory network - not further passable, leading to termination conditions and confusions of thought processes, derivations, or implementations. But what happens when the Flatland of the context is left and another contexture is added?17 Many of these dead ends could turn out to be passable paths that must be traversed through a transjunction; must be carried out into another dimension. The dead end does not appear as an end, the further path is only perpendicular to the previous plane; we have forgotten to look up. In the three-dimensional cube patience game ‘Inside Cube Mean Phantom’, a series of levels must be traversed to the final solution. On the cards embedded on two sides, some dead ends appear in each dimension, which are not dead ends but paths enabling passage to another dimension. The labyrinth, which a Western, analytically influenced philosophy of language games opens and is to be understood by Wittgenstein to warn us of dead ends, could thus also falsely and harmfully block important paths, which are only solved by applying another, coherent and consistent in itself, but in turn plagued by dead ends contexture. The contexture open up new paths for each other. The holes and dead ends prove to be places of opening. But each contexture remains distinguished by its own importance: The indication of connections from another contexture can, at least in this image, but also from other requirements through coherence, rarely be solved in the original contexture. As long as we have no other resolution of the world than through contextures that each follow the law of the excluded middle and are each coherently and contradiction-free constructed, which are equally powerful, our only seemingly open path remains to continue this representation of the contextures, with their respective openly apparent limitations. As well as to continue the connection of many contextures. This work attempts to improve the work on a contextures. In the image of the patience game, we could say that we do not yet have maps on the side of the cube. The theories we have are in a pre-cartographic state. The network aims to take steps towards mapping the world. Exploring the connections between the respective maps, i.e., the logic of their connection, the transjunction of contextures, will be an invaluable gain when several highly formalized contextures are available for comparison. At a later point in time, I hope to continue the work on connecting the contextures. Attempts are ready with Gotthard Günther. Graham Priest undertakes promising, partly differently laid attempts; currently, I suspect that Priest is on the right path and Gotthard will find little attention not only due to his high reception height. But much can also be learned from the attempts of the Indian monastic tradition of the Jaina, which began 2700 years ago [Kurzer_2023].

A good, that is, here dear and familiar theory is often confused with the world. No less convinced theorists see in proofs of errors in their theories, usually in a supposedly unconscious defense mechanism, difficulties in application, operationalization, or understanding of the theory. However, theories are always only throws; a net thrown over the world, necessarily deviating from it, hoping to capture it cartographically. For Karl Popper, theory is “the net we cast to catch the world --- to rationalize, explain, and control it. We work to make the meshes of the net ever tighter” [Popper_2002]. When the theory is used creatively, it is a draft. Drafts have their own level, which lies “more than >>just<< a third between idea and execution” [Krämer_2016 p.119]. In this level, associations are possible, they even offer themselves, which find no correspondence or implementation in reality. Sybille Krämer uses a non-functioning machine in a perfect functional diagram (ibid.), as well as the image of three chimneys ending in 4 feet, and the iconic infinite staircase of Escher, to illustrate the impossible objects that can be created in drafts (ibid. pp. 120-122).

If the theory is thrown over more than it can cover - applied to everything, regardless of where the boundary conditions fit - it is a discard; to be discarded or improved by determining the misdistance. Since we are already talking about throws: Ject as a syllable denotes a throw.18 The project is the throw ahead, with creative intent: A draft. An object is the throw ahead to look at it in peace. The object can also appear negatively connoted and legally as a reproach. The subject, the subjugated, demands the question of who subjugates whom here: For Althusser, it seems to be the subject itself, but learned through the SUBJECT of the ideological superstructure [Althusser_2010 pp. 84-99]. In the world of cognitively open to the environment, because operationally closed systems, it would be the system that always lays the distinction operationally to the ground. But both sides are part of a difference. Not to think of the system despite or against the environment, but systems are always in and only based on the environment. The separation of subject and object is not in different spheres. We do not need a spirit. No transcendental subject. Luhmann is therefore also a theorist of radical immanence.

Interim Result I: Theory Network as Form {#sec:Vision}

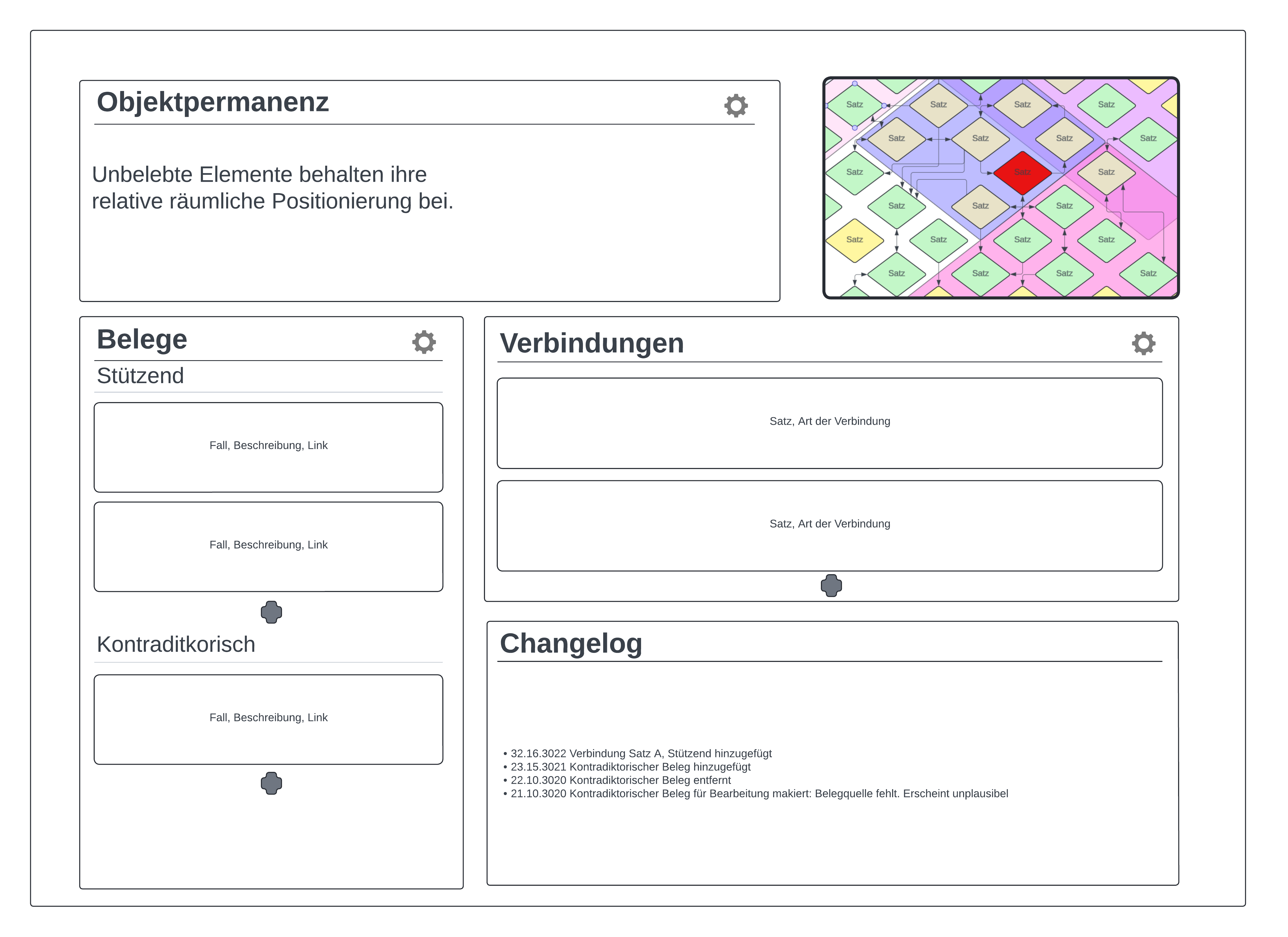

Here and in each subsequent chapter, requirements for a theory network, which is used in a collaborative endeavor, are collected and discussed in Chapter 6.3. To give the reader a clearer picture, a demonstration model, a mockup, is shown here in Figure 1:

|

|---|

| Fig. 1: Theory Network Mockup |

A page of the Wiki is shown; more precisely, a sentence page. In the upper left, a sentence is shown. The resolution is done here in general language. Other resolution types are also conceivable and indicated for application cases and groups. For simulations, for mathematical derivability, for the inclusion of system-theoretical forms, other formulations of sentences are conceivable. In the upper right, the placement of the sentence in the network of sentences is shown in dark red. The sentence is a central sentence; an anchor sentence. Navigation through related sentences is enabled via this map. More important will probably be the visual traceability of connections. Depending on the connection types, the edges of the network could each have their own visual markers. Color coding, symbols above the edge, among others, labeling, or thickness and continuity of the line are common markers here. Causal networks are certainly the most powerful networks for many application cases. They also pose a very high requirement for creation. Probabilistic influences could be displayed via a color scale. In the lower left, the area is shown where empirical evidence is collected that influences the sentences. In the case of central sentences, there should usually be few investigations here. At the outer edges are the observation sentences formulated for empirical testing; here it would be questionable whether these are created for each individual investigation and subsequently calculated into deeper sentences and dropped, or longer investigation chains are collected and evaluated for the individual observation sentences. In the middle right, the relevant connections to the sentence are shown. One could differentiate this according to incoming and outgoing connections; whereby both incoming and outgoing connections should make this differentiation difficult. Especially when checking sentences, these connections should be used and carefully examined. Here lies one of the clear advantages of a theory network and the collection in a shared Wiki, which we also want to note as a requirement for the conclusion. From the discussion of the Quine-Duhem hypothesis, we became aware of difficulties in inferring isolated hypotheses and deviant observations: 19 The problems of the Quine-Duhem hypothesis should be treatable, i.e., relevant theory parts should be visible depending on the question. This is achieved through the map and the connections. We certainly cannot meet the requirements of a Duhem holism; but the most likely observation-influencing or alternative explanatory factors, according to the best knowledge and conscience, are held here. In the lower right, we see the changelog. In addition to this sentence-specific collection of changes, further changes are collected at the network level. Changelogs collect all changes that have been made. Here, similar to the procedure for commits in multi-part teams in projects that are made with Git, changes are collected and a request is made as to whether they should be adopted. Only when these have been reviewed according to an established procedure are changes made. Each change entry then includes a brief description of the specific changes at the upper level; at a deeper level, a comparison of the versions with marking of the changed sections. Changes that add or remove evidence can probably be made in subversions. Changes to the statement of the sentence and central connections should be indicated by a version change. This change management plays an important role in the use of the theory network for publications: It can be traced under which theoretical assumptions the investigation was carried out, and how exactly the sentences used for the investigation have changed up to the time of the reader. This should greatly facilitate the exegesis and transfer of results and eliminate many sources of error in reception.

Literature

Abbott, Andrew (2001). Chaos of disciplines. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. isbn: 978-0-226-00100-5.

Abbott, Edwin A. (1884). Flatland: A romance of many dimensions. London: Seeley.

Althusser, Louis (2010). Ideologie und ideologische Staatsapparate. ger. 3., unveränd. Aufl. Gesammelte Schriften / Louis Althusser. Hrsg. von Frieder Otto Wolf. Hamburg: Westphälisches Dampfboot; Suhrmap,VSA. isbn: 978-3-89965-425-7.

Anicker, Fabian (2022). „Wie und wozu sollte man soziologische Theorien miteinander vergleichen?“ de. In: Soziopolis: Gesellschaft beobachten.

Asher, Herbert B. u. a. (1984). Theory-building and data analysis in the social sciences. 1st ed. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, in cooperation with the Midwest Political Science Association. isbn: 978-0-87049-398-0.

August, Vincent (2021). Technologisches Regieren: der Aufstieg des Netzwerk-Denkens in der Krise der Moderne. Foucault, Luhmann und die Kybernetik. ger. Edition transcript. Bielefeld: transcript. isbn: 978-3-8394-5597-5.

Baecker, Dirk (1998). „Editoral“. In: Soziale Systeme 4. url: https : / / www . soziale - systeme.ch/editorials/editorial_4_1.htm.

Derrida, Jacques (1976). Die Schrift und die Differenz. ger. 1. Aufl. Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch Wissenschaft. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. isbn: 978-3-518-07777-1.

— [2004] (2013). Die différance: ausgewählte Texte. ger. Hrsg. von Peter Engelmann. Nachdr. Reclams Universal-Bibliothek. Stuttgart: Reclam. isbn: 978-3-15-018338-0.

Duhem, Pierre (1954). The Aim and Structure of Physical Theory. eng. London: Princeton University Press. isbn: 978-0-691-02524-7.

Endruweit, Günter (2015). Empirische Sozialforschung: wissenschaftstheoretische Grundlagen. ger. UTB Sozialwissenschaften. Konstanz: UVK-Verl.-Ges. [u.a.] isbn: 978-3-8252- 4460-6.

Fuchs, Peter (1993). Moderne Kommunikation: zur Theorie des operativen Displacements. 1. Aufl. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. isbn: 978-3-518-58156-8.

— (2003). Der Eigen-Sinn des Bewußtseins. eng. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. isbn: 978-3- 8394-0163-7.

— (2008). Der Sinn der Beobachtung: begriffliche Untersuchungen. ger. Dritte Auflage. Weilerswist: Velbrück Wissenschaft. isbn: 978-3-934730-76-2.

Heilbron, Johan (Sep. 2014). „The social sciences as an emerging global field“. en. In: Current Sociology 62.5, S. 685–703. issn: 0011-3921. doi: 10.1177/0011392113499739.

Hirschauer, Stefan (2008). „Die Empiriegeladenheit von Theorien und der Erfindungsreichtum der Praxis“. In: Theoretische Empirie. Zur Relevanz qualitativer Forschung. Hrsg. von Kalthoff Herbert, Stefan Hirschauer und Gesa Lindemann. Suhrkamp.

22

Jaccard, James und Jacob Jacoby (2010). Theory construction and model-building skills: a practical guide for social scientists. Methodology in the social sciences. New York: Guilford Press. isbn: 978-1-60623-339-9.

Kant, Immanuel [1787] (1998). Kritik der reinen Vernunft. Hrsg. von Jens Timmermann. Philosophische Bibliothek. Hamburg: F. Meiner. isbn: 978-3-7873-1319-8.

Klüver, Jürgen (Juni 1991). „Formale Rekonstruktion und vergleichende Rahmung soziologischer Theorien“. de. In: Zeitschrift für Soziologie 20.3, S. 209–222. issn: 2366-0325. doi: 10.1515/zfsoz-1991-0303.

König, Gert und Helmut Pulte (2017). „Theorie“. de. In: Historisches Wörterbuch der Philosophie online. Hrsg. von Joachim Ritter, Karlfried Gründer und Gottfried Gabriel. url: https://schwabeonline.ch/schwabe-xaveropp/elibrary/openurl?id=doi%3A10. 24894%2FHWPh.5490.

Korzybski, Alfred (1933). Science and Sanity. 5. Aufl. New York: Institute of General Semantics.

Krämer, Sybille (2016). Figuration, Anschauung, Erkenntnis: Grundlinien einer Diagrammatologie mit zahlreichen abbildungen. ger. Erste Auflage, Originalausgabe. Suhrkamp Taschenbuch Wissenschaft. Berlin: Suhrkamp. isbn: 978-3-518-29776-6.

Kuhn, Thomas S. (2020). Die Struktur wissenschaftlicher Revolutionen. ger. Hrsg. von Hermann Vetter. Zweite revidierte und um das Postskriptum von 1969 ergänzte Auflage, [26. Auflage]. Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch Wissenschaft. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. isbn: 978-3-518-27625-9.

Kurzer, Kolja J. (2023). „On Taking Standpoints: Perspective Realism and the Teaching of Non-Onesidedness“. en. Göttingen.

Luhmann, Niklas [1979] (1981). „Unverständliche Wissenschaft: Probleme einer theorieeigenen Sprache“. ger. In: Soziologische Aufklärung 3: Soziales System, Gesellschaft, Organisation. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Imprint: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. isbn: 978-3-663-01340-2.

— [1984] (1991). Soziale Systeme: Grundriß einer allgemeinen Theorie. ger. 4. Auflage. Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch Wissenschaft. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. isbn: 978-3-518- 28266-3.

— (2009). Einführung in die Systemtheorie. ger. Hrsg. von Dirk Baecker. 5. Aufl. Sozialwissenschaften. Heidelberg: Carl-Auer-Verl. isbn: 978-3-89670-459-7.

— (2011). „Dekonstruktion und Beobachtung zweiter Ordnung“. ger. In: Aufsätze und Reden. Hrsg. von Oliver Jahraus. Nachdr. Reclams Universal-Bibliothek. Stuttgart: Reclam. isbn: 978-3-15-018149-2.

— [1990] (2018). Die Wissenschaft der Gesellschaft. ger. 8. Auflage. Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch Wissenschaft. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. isbn: 978-3-518-28601-2.

23

Martin, John Levi (2015). Thinking through theory. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. isbn: 978-0-393-93768-8.

Merton, Robert K. (1974). „The Normative Structure of Science“. eng. In: The sociology of science: theoretical and empirical investigations. 4. Dr. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Pr. isbn: 978-0-226-52092-6.

Opp, Karl-Dieter (2014). Methodologie der Sozialwissenschaften: Einführung in Probleme ihrer Theorienbildung und praktischen Anwendung. ger. 7., wesentlich überarbeitete Aufl. 2014. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden Imprint Springer VS. isbn: 978-3-658- 01911-2.

Popper, Karl R. [1934] (2002). Logik der Forschung. ger. 10., verb. und vermehrten Aufl., Jub.-Ausg. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. isbn: 978-3-16-147837-6.

Quine, W. V. (1951). „Two Dogmas of Empiricism“. In: Philosophical Review 60.1, S. 20–43. doi: 10.2307/2266637.

— (2011). From a logical point of view: three selected essays; englisch/deutsch = Von einem logischen Standpunkt aus: drei ausgewählte Aufsätze. ger eng. Hrsg. von Roland Bluhm. Mit einem Komm. von Christian Nimtz. Reclams Universal-Bibliothek. Stuttgart: Reclam. isbn: 978-3-15-018486-8.

Quine, W. V. und J. S. Ullian (2009). The web of belief. eng. 2nd ed., 27th [reprint]. New York: Random House. isbn: 978-0-394-32179-0.

Sapiro, Gisèle, Jérôme Pacouret und Myrtille Picaud (2015). „Transformations des champs de production culturelle à l’ère de la mondialisation“. fr. In: Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales 206–207.1–2, S. 4–13. issn: 0335-5322. doi: 10.3917/arss.206.0004.

Schlick, Moritz (1948). Grundzüge der Naturphilosophie. Hrsg. von W. Hollitscher und J. Rauscher.

— (2024). Gesamtausgabe. Abteilung 2 Bd. 2,2: Nachgelassene Schriften Naturphilosophische Schriften. Nachschriften, Diktate und Notizen 1922–1936 / Moritz Schlick. ger. Hrsg. von Konstantin Leschke. Bd. 2. Wiesbaden: Springer. isbn: 978-3-658-32126-0.

Schmidt-Wellenburg, Christian und Andreas Schmitz (Sep. 2023). „Divided we stand, united we fall? Structure and struggles of contemporary German sociology“. In: International Review of Sociology 33.3, S. 512–545. issn: 0390-6701. doi: 10.1080/03906701.2023. 2244170.

Seiffert, Helmut (1977). Einführung in die Wissenschaftstheorie. 2: Geisteswissenschaftliche Methoden: Phänomenologie, Hermeneutik und historische Methode, Dialektik. ger. 7., unveränd. Aufl. Beck’sche schwarze Reihe. München: Beck. isbn: 978-3-406-02461-0.

— (1980). Einführung in die Wissenschaftstheorie. 1: Sprachanalyse, Deduktion, Induktion in Natur- und Sozialwissenschaften. ger. 9., unveränd. Aufl. Beck’sche schwarze Reihe. München: Beck. isbn: 978-3-406-02460-3.

24

Slaughter, Sheila und Brendan Cantwell (Mai 2012). „Transatlantic moves to the market: the United States and the European Union“. en. In: 63, S. 583–606. issn: 1573-174X. doi: 10.1007/s10734-011-9460-9.

Sousanis, Nick (2015). Unflattening. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. isbn: 978-0-674-74443-1.

Stäheli, Urs (2000). Poststrukturalistische Soziologien. Einsichten. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. isbn: 978-3-933127-11-2.

Swedberg, Richard (2014). The art of social theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press. isbn: 978-0-691-15522-7.

— (2016). „Can You Visualize Theory? On the Use of Visual Thinking in Theory Pictures, Theorizing Diagrams, and Visual Sketches“. en. In: Sociological Theory 34.3, S. 250–275. issn: 0735-2751, 1467-9558. doi: 10.1177/0735275116664380.

— (2017). „Theorizing in Sociological Research: A New Perspective, a New Departure?“ en. In: Annual Review of Sociology 43.1, S. 189–206. issn: 0360-0572, 1545-2115. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053604.

Verhaegh, Sander (2018). Working from within: the nature and development of Quine’s naturalism. New York, NY, United States of America: Oxford University Press. isbn: 978- 0-19-091316-8.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig [1984] (2019). Über Gewissheit. ger. 16. Auflage. Werkausgabe: [in 8 Bd.] / Ludwig Wittgenstein. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. isbn: 978-3-518-28108-6.

Zermelo, Ernst (2010). „Über den Begriff der Definitheit in der Axiomatik - 1929a“. eng ger fre. In: Collected works: Gesammelte Werke. Hrsg. von Heinz-Dieter Ebbinghaus, Craig G. Fraser und Akihiro Kanamori. Schriften der mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Klasse der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften. Heidelberg: Springer. isbn: 978- 3-540-79383-0.

Footnotes

-

This epistemological argument follows the Duhem-Quine hypothesis, primarily outlined in the works [Duhem_1954] and [Quine_1951]. This epistemic holism plays a rather subordinate role in the master’s thesis. ↩

-

The chapter references pertain to the master’s thesis in its submitted form. For those interested and with time, it can be found here: Kurzer - 2024 - Wiedereintritt des Systems Theorie als Netzwerk Reentry of the System Theory as Network.pdf However, it is exclusively in German. ↩

-

Formally, this can be directly derived from modus ponens (affirmative mode of logical inference): If are true, then O is true; if O is not true, it follows that at least one hypothesis to is not true; it neither follows which one nor how many are untrue. ↩

-

Unless you happen to have a background in analytical philosophy and systems theory, or a functional equivalent, this sentence will be difficult to understand. Please overlook this. The terms of the sentence are addressed in the thesis, particularly in Chapter 5.1. ↩

-

I, not you, but also they. ↩

-

Quine is cited in seven places in The Science of Society ([1990] (2018). Here it is already much further removed from typical pragmatist or other analytical considerations, such as a naturalistic epistemology, than in, for example, Social Systems. ↩

-

“None of these properties is preferable to the other. Without sensibility, no object would be given to us, and without understanding, none would be thought. Thoughts without content are empty, intuitions without concepts are blind. Therefore, it is just as necessary to make one’s concepts sensible (i.e., to add the object in intuition to them) as to make one’s intuitions understandable (i.e., to bring them under concepts).” - Kant KrV A52/B75 quoted after Kant [Kant_1998]. ↩

-

Books that centrally address theory methodologies are usually more open to social sciences or science: [Seiffert_1977; Seiffert_1980] & [Asher_Weisberg_Kessel_Shively_1984] & [Jaccard_Jacoby_2010] & [Opp_2014]. John Levi Martin’s book directly aims at improving theory and theorizing in sociology [Martin_2015]. The works of Richard Swedberg are primarily practice-oriented [Swedberg_2014; Swedberg_2016; Swedberg_2017]. ↩

-

C: Communism; U: Universalism (This, in my opinion, needs to be renegotiated, there are good reasons for and against); D: Disinterestedness (This point might also not be justifiable for some groups); O: Organized skepticism. ↩

-

Probably something like a theory wiki for each hyphenated sociology, until convergences emerge. Or vice versa, a common one, until the hyphenated sociologies differentiate into their own. ↩

-

I got this formulation from Peter Mönikkes; he could no longer find the source. ↩

-

Wiki is a portmanteau of the Internet and the encyclopedia. I consistently use the feminine gender here. ↩

-

Remarkable in this, the axiomatics underlying almost all of today’s mathematics and logic, is that it was observed as contingent by its founder Ernesto Zermelo himself (cf. Chapter [sec:TypolSätze]{reference-type=“ref” reference=“sec:TypolSätze”}). ↩

-

A rather misleading description of the behavior of electrons; the physical subtleties are in the background here; it is about the shifts that were sociologically observable. ↩

-

With this image, a strong argument can also be made for creating different theory networks, each abstracted to varying degrees, for different tasks. Just as maps for navigation on foot and for orientation by sight in a glider would not be suitable at each other’s resolution depth. ↩

-

The term contexture stands between context and texture. It can then be understood as a tracing of the lines of forms that a specific theory makes visible in the world. It is thus a more formal and less far-reaching version of an ideology or worldview concept. I lean less on Gotthard Günther here than the context of Luhmann’s engagement and the references to Günther might suggest. It is still quite a murky fishing in these border areas, of and between theories. ↩

-

An allusion and homage to the book Unflattening, and the book Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. Unflattening is the first dissertation in comic format; it opens up many of the ideas pursued in this paragraph and many hundreds more. In it, the power of visualization for theorizing and understanding in general is demonstrated, as far as I know, in a way that no comparable work does [Sousanis_2015; Abbott_1884]. ↩

-

The fundamental idea of the importance of throws for human language, I owe to a lecture by John Vervaecke; whether this applies only to Western languages and represents a misguided universalization, I have not checked. ↩

-

These requirements are continuously numbered with . ↩